What the Doom-and-Gloom About Automation Tells Us About Remote Work

Barry Nyhan

Senior Demand Gen & Marketing Ops

16 Aug 2022

In less than five years automation has gone from the workforce’s greatest threat to its most promising solution. Can the same be said for remote working?

It might feel like an eternity has passed – thanks to the pandemic and other monumental global events – but just a few years ago the world was in a panic about a scary economic boogeyman: automation.

At the height of the automation panic roughly five years ago, organizations like McKinsey, the Brookings Institute, the OECD, and PwC published in-depth studies about a workforce in transition. What my colleagues in the media tended to focus on, however, were the big numbers at the very top of those reports.

Automation could kill 73 million U.S. jobs by 2030 U.S. jobs by 2030, warned USA Today in November of 2017. Robots will destroy our jobs – and we’re not ready for it, according to the Guardian in January of 2017. Robot automation will ‘take 800 million jobs by 2030’’ read a headline published by the BBC in November of 2017. Automation threatening 25% of jobs in the US exclaimed CNBC in 2019.

Those like myself who were responsible for digging a little deeper into these studies, however, found a situation far less dire than what those headlines suggested. Yes, lots of jobs that existed in the mid-2010s would not exist a decade or two later, but automation and new technologies would also create significantly more new jobs in categories and industries we couldn’t yet imagine.

Meanwhile, those jobs and roles that were not automated out of existence would become easier and more pleasant for human operators.

There was another factor that we also skipped over in our haste to make splashy headlines go viral five years ago. Though we didn’t know it at the time, we would soon be in a situation where just about every industry was short-staffed. Now all of these digital tools that can improve efficiency, reduce human error and yes, render certain jobs obsolete, can’t come to market fast enough!

Why I didn’t panic about automation (and why I won’t about remote work)

In 2017 the idea of needing fewer baggage handlers at the airport, or servers in the restaurant, or having a more automated global supply chain seemed like a doomsday prediction. Now, inflation is on the rise in these and nearly every other sector because there simply aren’t enough workers. In less than five years automation has gone from the workforce’s greatest threat to its most promising solution.

Tempting as it was to panic back in 2017, there were two things that kept me from seeing automation as the workforce boogeyman the headlines claimed it to be.

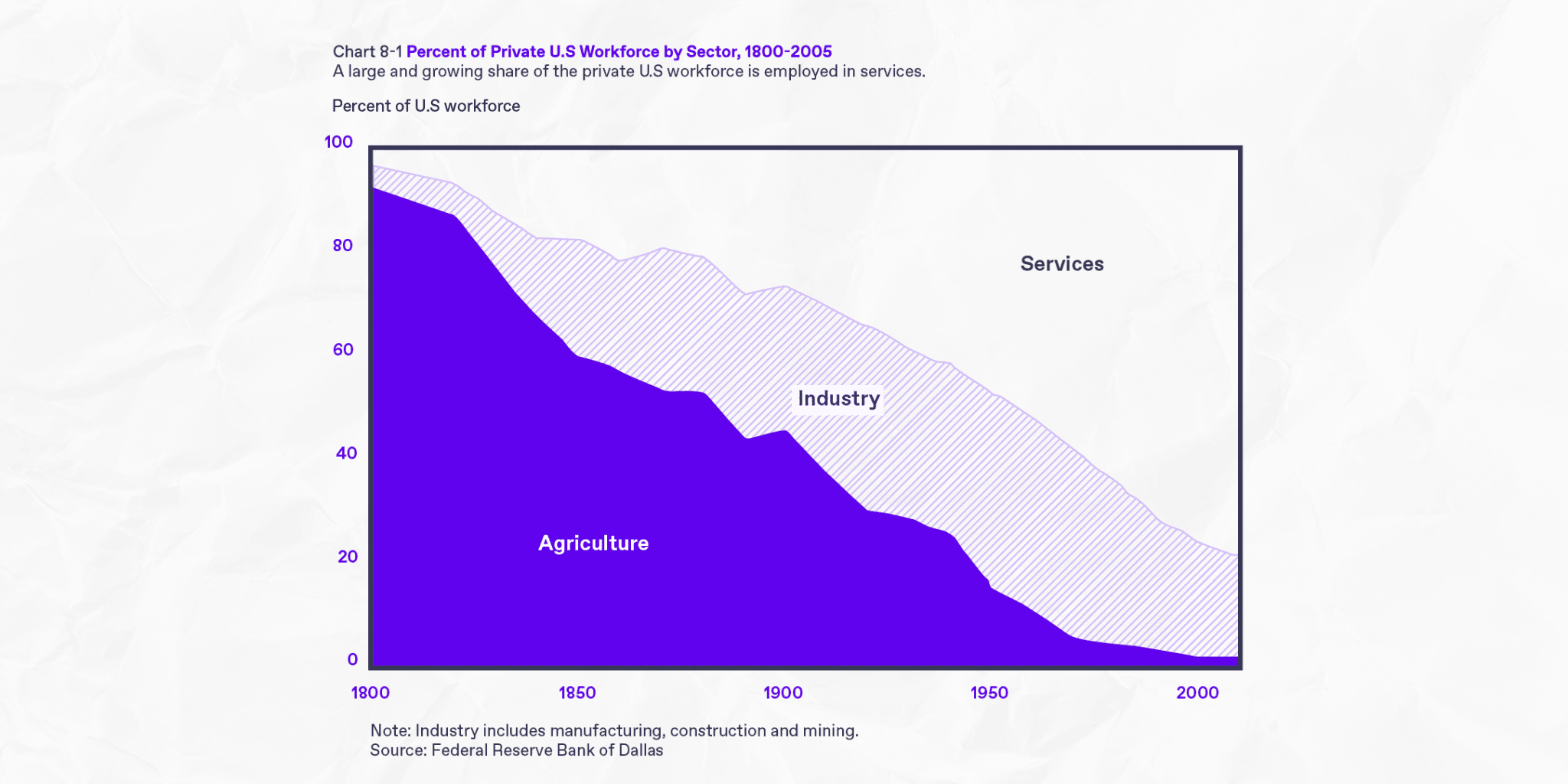

The first is the chart above. This is not the first time that technology has eliminated a huge number of jobs in a relatively short period of time. In the early 1800s new technologies dramatically reduced the labor needs of what was then the world’s largest employment sector: agriculture. These tools made food production less manually intensive, and agriculture jobs dried up. At the same time, however, a new industry was emerging: manufacturing (referred to in the chart above as ‘industry’).

The workforce wasn’t disappearing, but rather in a state of transition, with far-reaching implications on not just jobs, but society as a whole. For example, the transition from agriculture to manufacturing required many to adopt new skills; work became an indoor activity, with a designated time and place; everything was standardized and optimized for efficiency; and many workers had to transition from rural to urban living to find work opportunities. While the transition wasn’t smooth for everyone, work remained plentiful.

Now we are seeing the same pattern repeating itself. People were so focused on the roles that were at risk of being eliminated, they lost sight of the new opportunities that were emerging around them. Despite many jobs being automated out of existence, we still don’t have enough workers to fill open positions.

Going digital rather than disappearing

As McKinsey, the Brookings Institute, the OECD, and PwC all pointed out in their original analysis, the challenge isn’t that jobs are disappearing, it’s that the workforce is once again being challenged to adapt to a new kind of economy – one where jobs increasingly exist in a mostly or entirely digital space.

Ironically, this workforce transition also has the potential to reverse many of the trends introduced during the last major workforce upheaval. Remote workers are now leaving cities for more rural destinations, and longstanding models of standardization – like the 9-to-5, Monday-to-Friday standard – are being challenged, as is the need for a centralized workplace setting.

The other thing that stopped me from panicking about automation back in 2017 was that I personally witnessed the creation of a new industry over the course of my university studies. I might be dating myself here, but I entered a media studies undergraduate program at a time when Facebook still required an invitation from an existing member to access the platform. By the time I graduated, Facebook had over a billion users and Instagram had been invented, as had YouTube and Twitter.

When the program began, ‘media’ was considered to be movies, books, TV shows, and magazines. By the time we graduated, a large proportion of my classmates had begun promising careers in digital media – an industry that didn’t exist when we had started the program four years prior.

The takeaway for remote working

So, what can we learn from the great automation panic of the mid-2010s? I hope it serves as a reminder of how far off these gloomy predictions (or at least the headline versions of them) tend to be as we enter another major workforce evolution.

Just as automation didn’t kill the labor economy, remote and hybrid work won’t kill cities, or company culture, or our trust in each other, or our social skills, or our mental health – despite countless headlines that say otherwise. We are simply in a state of transition, similar to the countless workforce transitions that have come before.

Based on those prior experiences, we know that many of our fears will prove to be unfounded; that when we talk about the long term we’re much more adept at pointing out potential problems than imagining potential solutions; and that those who lean into these changes, rather than denying or resisting them, typically enjoy a smoother transition.